An Individual Preference Driven World

____________________________________________________________________________

General Ideas

Philosophical Assumptions

Human happiness is undefinable and incalculable

Human preference is a result of constant evaluation of available options

Maximizing options available to individuals is the best way to maximize “happiness”

We cannot tell others what makes them happy - “scientific optimization” is not useful in societal realm

“Means” are more important than “ends”

Economic Implications

Demographics drive changes in economic and societal structures

Dependence on altruism is not scalable

Property rights as an emergent, selfish, net positive set of voluntarily agreed upon rules

Human preferences translated into trade

Medium of exchange as a way to expand ability to meet individual preferences

Importance of sound/hard money in translating human preferences to the market

Downsides of soft money: Distortion of money as deprioritization of some people's preferences

Emergence of central banking

Changes in central banking

General implications

What about the political issues of today?

What does this mean for our democratic system more generally?

____________________________________________________________________________

Philosophical Assumptions

Human happiness is undefinable and incalculable

Happiness is an abstract idea. It cannot be evaluated in the same way that an object or material can be evaluated. You cannot measure happiness in pounds, dollars, or distance. We use the word happiness not as a scientific term, but as a way to express positive experiences and feelings we have. The most accepted approach we have taken to try to “define” happiness, is to identify correlations between the state of the material world when these “happy” experiences reveal themselves to us. This approach has left us with the conclusion that leisure time, time in nature, and time with close friends and family is the key to happiness.

While this correlation may exist if we look at averages across societies, it is not a scientific cause and effect relationship for all people for multiple reasons. First, self reported levels of happiness are incomparable. If two people were both to rank their level of happiness at 4 on a scale of 1-5, does this truly mean their experiences have the same “level of happiness”? Of course not; because happiness is a subjective experience of individuals, there is no effective way to compare these experiences through our traditional scientific process that is designed to understand properties of materials and substances (physics, mathematics, chemistry, etc.). Second, on an individual level, there is no certainty that one is to be “happy” when with family, friends, or in leisure, and there is even no certainty that one not in these circumstances is unhappy.

These observations lead me to believe that it is a fool's errand, and arguably immoral, to try to structure a society from the top down to maximize happiness, an inherently undefinable metric. A society maximizing for a simplified and impossible to define happiness necessarily does not put actual preferences of individuals as the key driver of society.

Human preference is a result of constant evaluation of available options

We as humans are constantly evaluating a range of potential actions. Each action we make is by definition the one that in that moment is preferable over all other actions we could take. Therefore, these actions are always made in a self interested manner. Examples of this are inexhaustible because we as humans are acting (changing behavior based on preferences) constantly. For example, by sitting down and writing this sentence, I am revealing to the world that this is what I prefer to be doing in this instant, over all other possibilities. This concept is constantly active within all humans, animals, and one could make a case for plants and inorganic materials too.

At its most basic level, value judgements are constantly being made between the full range of options available to us, and these value judgements result in a preference, which results in action. If we look at an animal example; a salmon swimming upstream to lay eggs is valuing the likelihood of creating offspring greater than the consequence of being eaten by a bear on this journey upstream. This concept is valid whether or not there is an agent, or a “self” acting on these value judgements. To give another example from the organic world, plants prefer certain reproduction strategies over others. While dandelions have short lifespans and light seeds that leverage the wind to maximize potential landing places for future offspring, oak trees maximize for robustness of seeds, and rely on a higher “conversion rate” per seed to reproduce. These strategies were selected naturally in a Darwinistic way. We can think of these strategies as an expression of these species’ “preferences”.

Because we as humans are more evolutionarily advanced, both biologically and socially, than plants and most animals, our range of available options to evaluate is huge in relation. Mises uses the word action to describe the result of these value judgements, but I like the use “preference” because it is less associated with the idea of an agent making decisions, and more inclusive of worldviews that are strictly materialistic or believe there is no free will. Think of all the things you could be doing right now, or how what you have done so far today could be different. Because we are self interested animals, what we do and prefer is the best representation of what is important to us, and what helps us strive for the ever elusive experience of “happiness”. This serves as the main reason why I believe human preference should be the key data input into the economy; the economy should constantly be evolving to deliver to people their most preferable future. This previews my view on what a moral economy looks like.

While I’m centering this idea around human preferences that primarily serve to maximize “happiness”, this doesn’t overlook more essential needs required for survival. Taking care of these essential needs (shelter, heat, food, etc.) is a prerequisite to widening the range of choices humans could be exposed to. In a primal world, humans have a narrow range of choices available to them throughout their day because all their actions (that take up essentially all waking hours, as we are constantly selecting between options) are taken to ensure near term survival. For example, let’s imagine there is no option available to this hypothetical primal human to not catch 10 fish this week, and instead spend time building a more permanent home, leading to almost certainly a wider range of choices available to this person in the future. Catching the fish is required for survival, so time spent developing tools and useful technology that would eventually lead to exposure to additional ways to spend one's time (art, music, thinking, inventing, etc.) is never an option available to this individual.

The number of choices available to someone is a good indication of the effectiveness/evolvedness of the society; a member of a hunter gatherer society has a limited set of options available to them because survival is so front and center; a thriving society with wealth, free time, creative businesses, and services aimed at meeting preferences of others reveals a wide set of options for citizens to choose between when allocating their time; and authoritarian regimes, while they can be technologically advanced, have a poor ability to identify preferences of individuals, and therefore the range of choices available to people falls substantially. I think that in the last 20 years the US economy has devolved if we use the above definition.

Maximizing options available to individuals is the best way to maximize “happiness”

My proposed alternative to a “happiness centric” society, is a society that aims to maximize the range of choices available to humans in society. This alternative model reveals itself due to the assumption that happiness is immeasurable, and that we always are evaluating potential options and act in our most preferred manner; in a self interested, happiness maximizing way. As mentioned before, happiness isn’t quantifiable, but options can be evaluated as more or less preferable than others. Notice this is a fully relative relationship, and is only valid within an individual.

For example, If I prefer an ice coffee over a hot coffee, this does not mean that you also share this preference. My preference doesn’t give me evidence of your preference. Also, it can’t be said that ice coffee is X times as preferable than hot coffee; how would one reach this conclusion? There may be a time in which this preference changes to hot coffee, and in this case the only “data” we can extract from this information is that at one time I preferred iced coffee over hot, then later I preferred hot over iced; there is no clean formula that can mathematically calculate my relative preference over time, it is simply a binary preference at any given moment in time. It is useful for society to identify preferences that prove themselves to be predictable, as this can be a reason for investment in a solution that will deliver this preference to people. A static pattern emerges between a binary option if, say, 98% of the time this person chooses to eat breakfast instead of buying a t-shirt. All else being equal, it would be better to invest in a food business, because if the past is any indication of the future, it will meet more preferences than a t-shirt business. That is getting more into the economic realm.. but the main point here is that preferences are relative, not measurable evaluations of options, and that they are not comparable across people. If we can’t quantify the strength of preference we feel within ourselves, how can we know the strength of preference of others? We can’t, we must let them tell us through their preferences captured by the market.

Now let’s consider a circumstance in which someone has a wide range of potential choices/actions available to them. Now let’s imagine that this range of potential choices/actions is cut in half. While one cannot calculate the numeric decrease in expected happiness that is no longer available to this person due to this limited selection of options, one can assume that as the number of available choices decreases, the likelihood that one’s initially most preferred choice is still available to them also decreases. Because we make decisions (act on preferences) in a self interested and happiness maximizing way, we can reach the conclusion that by limiting the number of options available to people, we are limiting their potential level of happiness.

A paradoxical idea has emerged in the last 50 years as a result of an increase of consumerism sentiment: people now commonly report getting overwhelmed by choices and would prefer fewer options. I view this challenge of choosing between many in a completely different way than real-resources-driven choice limitation. By real-resources I mean actual real word impacts, such as the status of technology, food, war, commerce, business, etc. Your choices are minimized by the external factors resulting from these real-resources impacting the world . In the case of “too many options/choices”, one can simply eliminate options if one’s preference is to evaluate fewer options. If this person continues to evaluate more options than they said they prefer, they’re actions reveal their true preference; they prefer more options. Reducing your options is always in your control, increasing them is not.

Obviously there could be cases in which an increase in available choices for one individual could be associated with limiting the scope of available choices for someone else. This I believe is best discussed through an economic lens, and is addressed through protection of property rights that I will discuss later on.

Takeaways that are key to economic implications

We cannot tell others what makes them happy - “scientific optimization” is not useful in societal realm

Because happiness is an immeasurable experience: it is not something that can be counted, added, subtracted, or handed to others. Due to these imprecise properties of happiness, one cannot design a society that maximizes happiness in the same way that an architect can maximize the strength of a building through design choices that leverage the laws of physics. We understand the properties of materials like wood, steel, and cement. We understand concepts such as torque, gravity, force, and momentum. But we don’t understand the properties of happiness. Therefore, we should not treat happiness as strictly a scientific optimization problem. This is the same trap Keynesian economists fall into with the economy.

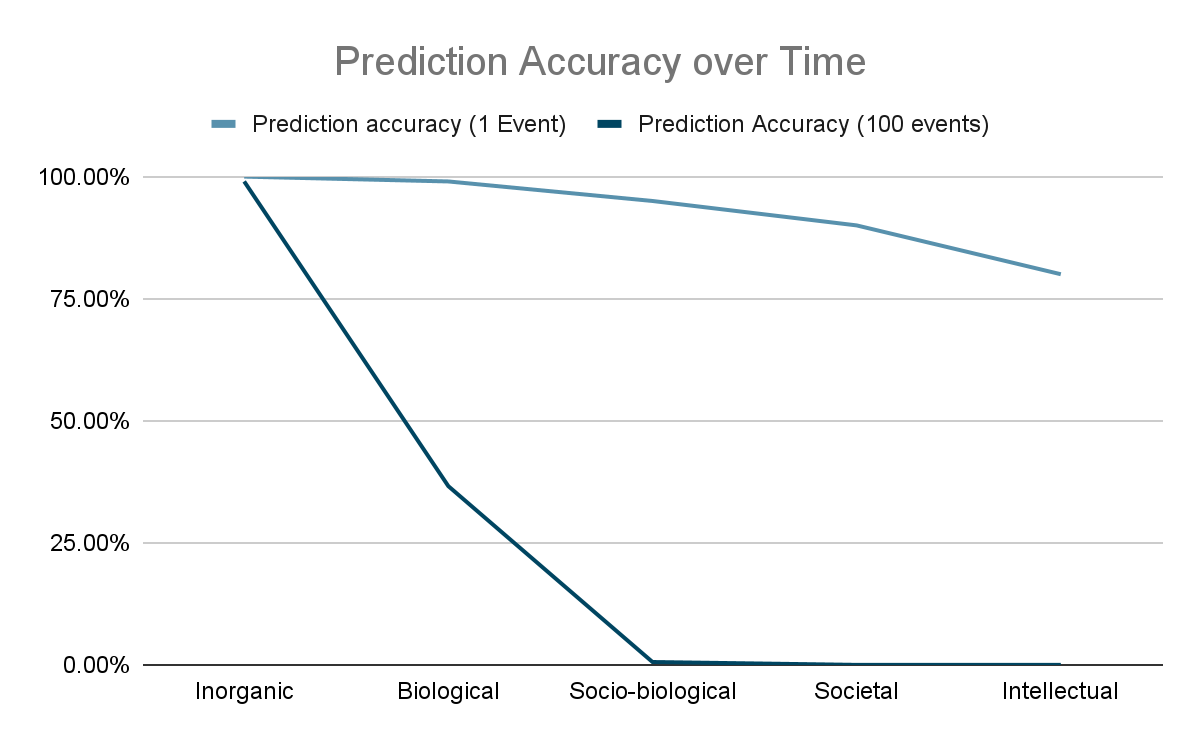

This statement is the result of a foundational metaphysical question: can we treat society and politics as a field of science? There are very compelling perspectives on each side of this argument. My current thinking on this question yields the answer “technically yes… but it’s not useful”. I think Pirsig’s “Metaphysics of Quality'' provides the most appropriate lens through which to view this question. Scientific observations are possible at all levels of evolution: inorganic, biological, social, and intellectual, but we have greatly different “confidence intervals” in our prediction of future events. We have a very strong understanding of inorganic events; think of gravity, physics, physical properties, etc. If one thinks of all events in the world as the result of a collection of forces at any given moment, expected results can be “calculated” and predicted, with a level of confidence. The level of confidence is effectively our prediction “conversion rate”. We are almost 100% confident that when we drop a stone from our hand that it will fall towards the center of the earth. Similar, but not quite as accurate, “predictions” can be made about organic and biological responses to situations in the world. We are (for example) 99.5% confident in predicting the response of a plant to a certain external stimulus. These levels of confidence are very high, and can be useful in making predictions about the future. Our levels of confidence are substantially lower when dealing with societal and intellectual predictions. These aggregate levels of confidence are immeasurable, and we should approach all “predictions” independently, but I think it’s safe to say we haven’t been able to predict societal or intellectual changes with the same success as inorganic or even biological. We have a few ideas for how societies will respond to stimulus, but these responses are very hard to measure, let alone predict. The difference in confidence in our “predictions” for the future are exacerbated when we look at compounding, or layering predictions over time (i.e. A will cause B, B will cause C, etc.). Let’s look at a visual example of this. In the example below I assume our level of confidence for predicting inorganic, biological, socio-biological, societal, and intellectual events is 99.99%, 99%, 95%, 90%, and 80%, respectively. In order to predict at all into even the near future, we need to link events together as time passes. We can see that after 100 events, the accuracy of our predictions ranges greatly: We should be confident in inorganic predictions, but not at all in societal or intellectual predictions.

The implication of this is important: We can use the scientific method on any medium we’d like, but the results cannot be treated equally. Our accuracy of prediction and the passage of time (event stacking) reveals the reality that it is useful to use scientific optimization (planning and manipulation of future states of mediums) for mediums we have established prediction accuracy for (physics, chemistry, etc.), but not for societal and intellectual realms; usefulness deteriorates quickly as we compound predictions.

The means are more important than the ends.

This takeaway consists of two main observations. First, the idea of an “end” is a useful abstraction for us, but doesn’t actually exist. How do you know when you reach an “end”? And even if we assume we can reach an “end”, say, that less than 5% of the population lives below the poverty line (an arbitrary measure.. But let’s leave that aside for now), time doesn’t stop. We aren’t in a static system, and we as humans require continued consumption to survive. Reaching a targeted “end” is a useful abstract idea for humans to latch onto, but as we know through psychological studies, the accomplishment of a defined “end” like getting into college, or getting a new job, or buying a new house, does not have an outsized positive impact on one’s happiness. While I think these studies are faulty due to the immeasurability of happiness I described before, even their questionable methodology supports the claim that “ends” are not the key to happiness! Second, even if we assume “ends” are important, they are “reached” so infrequently that it feels as if we are sacrificing the vast majority of our time in order to reach an “ends” that is supposed to make it all worth it. Keynesians fall into this trap with inflation targets, GDP, CPI, and other “scientific” measurements of an economy that is driven by preferences with immeasurable properties. Shouldn’t we flip that around and prioritize the vast majority of time in which people are making preference based choices in order to meet their needs and improve their personal happiness? I think so.

____________________________________________________________________________

Economic Implications

Demographics drive changes in economic and societal structures

Demographic changes create the need for new and often more complex social structures. New social structures and associated economic norms are formed to best accommodate demographic changes; so far throughout history, these demographic changes are primarily population growth. In areas where societies and economies do not evolve to accommodate a higher population, the population will continuously approach the natural carrying capacity of this societal/economic structure, then fall into turmoil and restart this cycle. Let’s look at a few examples of how I imagine demographic change created the impetus for new economic structures.

In hunter-gatherer tribes, there were no transactions that we would today consider economic trade. These tribes generally had individuals who specialized in certain activities; the traditional example of men hunting game and women gathering plants and taking care of children is applicable. A characteristic of these tribes that is more useful for comparison to future economic structures is that people shared resources willingly and without accounting for who shared what and how much of it. This is only possible through trust. This trust is possible because these tribes were small enough that all members had a personal relationship with one another. (Many studies have shown that the number of personal and trusting relationships one can have with others is around 150. Modern companies have found success with limiting office sizes to this size to maximize employee engagement, trust, and teamwork.) Note that the sharing of resources in these tribes is not evidence of altruism, but self centered action. If a member of the tribe were to continuously take advantage of this trust based sharing mechanism, they would likely be ostracized from the group. On the other hand, the most sharing, reliable, and honest member of the group will gain trust, and reap benefits from this trust throughout his or her life.

It is when tribes settled in static locations and began to grow and merge, that new societal norms and structures were required to enable the sustained survival of a group of individuals with never before seen demographic characteristics.

Property rights as an emergent, selfish, net positive set of voluntarily agreed upon rules

To understand how property rights evolved, we should understand the first societies that settled in one place and experienced any kind of meaningful population growth. As described above, small groups can function without defined property rights due to trust, and an outsized focus on near term priorities. But when groups grow and begin to want to be able to plan for the future, property rights were voluntarily agreed upon in a bottom-up, naturally occurring way in order to create some predictability of society.

It seems to me that property rights acted as a solution to an unmet need in these early societies. As groups grew beyond the scale in which trust and reputation were a big part of how one secured future support from group members, theft must have become a rampant problem. If there was a neighboring group with resources that another group wanted, there was no social restraint mechanism that would discourage stealing from the other group. Rather, engaging in this dangerous act of theft may well be viewed as another trust building act within your group. This scenario likely acted as a temporary ceiling on societies’ population growth for a long period of time. The first set of groups to realize that voluntary trade and acknowledgement of rights to ownership of land, resources and technology would be beneficial for all parties involved “discovered” the value of property rights. This shift can be viewed in a game theoretic way.

Members of the first generations to engage in group conflict likely reaped no benefit from acknowledging other people's property rights. For example, if two groups were to meet, and one respects the other's property while the other does not, the group that doesn’t respect property rights will pilfer the group that doesn’t engage in stealing. This was likely the state of affairs for a long time. Over time, as the natural population ceiling for non-cooperative societies was continuously bumped up against, but never surpassed, groups likely started to realize that if they wanted more safety and predictability for their own, and their children's, futures, a new set of societal rules must be agreed to. Property rights are essential to these new societal rules. This concept can be observed in multiple historical accounts, but I'll provide one quick example Bertrand Russell provides in “The History of Western Philosophy”.

“A new element came with the development of commerce, which was at first almost entirely maritime. Weapons, until about 1000 B.Cb were made of Bronze, and nations which did not have the necessary metals on their own territory were obligated to obtain them by trade or piracy. Piracy was a temporary expedient, and where social and political conditions were fairly stable, commerce was found to be more profitable (i.e. optimal game theoretic strategy). In commerce, the island of Crete seems to have been the pioneer. For about eleven centuries, say from 2500 B.C to 1400 B.C., an artistically advanced culture, called the Minoan, existed in Crete. What survives of Cretan art gives an impression of cheerfulness and almost decadent luxury, very different from the terrifying gloom of Egyptian templates.”

To be clear, the property rights I’m referring to mean that one has the right to own, store, save, and consume the fruits of their labor as they prefer, unless this consumption infringes upon another person’s property. These first forms of property likely initially took the form of basic shelters, tools, food, and clothes. Eventually, the range of items that fall under this umbrella expands with invention and technological development (homes, cars, savings).

Property rights enabled individuals and groups to start to think and plan into the future, as the likelihood of being able to effectively reap future benefits from today’s labor increased because what they have today is more likely to be there in the future due to this new social contract. Once a sufficient number of people agreed that they would prefer this set of “rules”, the optimal game theoretic approach shifts, and those who violate property rights are ostracized or potentially killed as a deterrent, and those who respect property rights thrive. The optimal strategy shifts to respecting property rights not because it is “human right”, but because it is the preferred choice of each individual to be a rule-abiding member of this society. This is the default worldview the Western world has subscribed to since the Enlightenment.

Human preferences translated into trade

So now we have established property rights as an essential ingredient of social stability at any meaningful scale. What does this stability enable? Planning for the future, trade, specialization, savings, and eventually the capital investment that we’ve seen in the last few centuries are all the results of strong property rights.

But all this started with trade. Trade, by definition, emerged at the same moment that individuals (or small tribes) no longer produced everything they consumed. In order for this exchange to happen, ownership of the contents of these trades must have been recognized. Therefore, we see property rights, trade, and mutually beneficial cooperation between strangers (non-trust based relationships) emerge all at once.

Trade is an expression of preferences by two parties. A trade only occurs when person 1 prefers good B over good A, and person 2 prefers good A over good B. If this trade is not preferable by both parties, then it becomes a violation of property rights through coercion. It is in the microeconomic range where we best understand economics because it is the only level of economic analysis that isn’t trying to leverage a scientific approach to a medium (human preference) that we can’t measure. We still get ourselves into trouble by extrapolating future expectations based on previous trades. For example, if yesterday I exchanged a cup of coffee for 2 muffins, it doesn't mean that I will prefer that same trade in the future. The more samples we have of this transaction being consistent over time, the more reasonable it is to base future investment on this data. But the point stands regardless: preferences are dynamic and constantly shifting in all people.

Medium of exchange as a way to expand ability to meet individual preferences

The economic scalability of direct trade of goods and services is very limited without a medium of exchange. For example, if there are three people; 1, 2, and 3, that have goods A, B, and C respectively, and would prefer to have goods B, C, and Z, respectively, in an economy of strictly direct trade there would be no exchanges made. Person 2 has what person 1 prefers, but person 1 doesn’t have what person 2 prefers, so no voluntary exchange can be made. To enable this transaction, person 1 would need to acquire good C from person 3 to then exchange good C to person 2 for good B. The key here is that there needs to be a way for person 1 to provide value to person 3 even though he or she has no goods/services that person 3 desires. This is the role of money. The moment that something emerges to fill this role, the amount of trade soars, and therefore more preferences are able to be met.

This role of money can be thought of as a medium of exchange. We can for the moment ignore the role time plays in money. Mediums of exchange likely initially emerged through goods that were desired by a large majority; think grain, water, seeds, etc. To complete the above example, if all three people also had and desired seeds, then person 1 could acquire good C from person 3 in exchange for seeds, and then the preferred exchange between person 1 and 2 can be completed.

This limiting characteristic of the initial mediums of exchange emerged once we consider time. Specifically, will this medium of exchange hold its exchange value over time? If we think of the examples above, the answer is no. Grain can be produced, water can be collected, and seeds reproduce naturally. If the use of a medium of exchange is dependent on the immediate consumption of the medium itself (water for example), or another instantaneous trade with the medium before it’s value is lost (grain going bad), then the number of trades that are preferable to people is limited because this medium of exchange loses value quickly over time. If my medium of exchange cannot be kept on the shelf for a week, I would not prefer to trade for this medium unless I had another near term trade I wished to make. This introduces the idea that mediums of exchanges that also maintain value over time make a whole range of trades economically viable. And when more trades are made, that can be viewed as more preferences being met.

Importance of sound/hard money in translating human preferences to the market

So in this “utopia”, all people’s preferences would be expressed through demand for goods or services, and translated into prices. This in turn incentivizes business and individuals to serve these preferences of others because it is beneficial to themselves. The accuracy of these price signals is paramount, as they are the direct incentives that drive investment into solutions that are most important to the greatest number of people. You could think of it as an emergent, constantly updating, distributed database representing the preferences of people in a society. This isn’t a new idea; it’s the same free market idealistic laissez faire model you’ve heard about. The thing is, it is unquestionably the best way to reflect the preferences of a large number of individuals. For this preference to demand, demand to price, price to incentive, incentive to production cycle to reflect the preferences of all people fairly, the money used in this pricing mechanism needs to be sound.

A sound, or hard, money is a money that has a very low change in total supply over time. This means that if you have 1/100 of the total money today, you will have a very similar percentage of the total money at a time in the future. Your savings are not diluted. The benefits to society of using sound money is not a theory, but can be observed empirically throughout history. What is identified as a good to be used as money is also a market phenomenon, something that is often completely ignored today. Since trade began, humans were looking to ensure these “money goods” would still be valuable in the future. Scarcity is the trait most desired. Humans went from voluntarily using rocks and shells and other somewhat scarce goods as money, and over time shifted to silver and eventually gold. It’s worth noting that gold and silver emerged as money in societies that never had any previous contact before; this represents an essentially airtight case that certain properties are best suited to play the role as money. This is not equivalent to a scientific consensus (where a vast majority of scientists share their opinion), but comparable to independent replication, a much stronger piece of evidence.

Before getting into the downsides of soft money systems, I want to reiterate that the foundational reason sound money is effective is because it does the best job of providing the market with accurate prices, and these prices directly reflect the preferences of all market participants. This is the key to a “human choice centric” society.

Downsides of soft money: distortion of money as deprioritization of some people's preferences

It’s often easier to describe the downsides of soft money rather than the benefits of hard money because we generally learn to think about the economy as if we are always using hard money. Here are a few of the most significant downsides of soft money.

Inflation and a loss of purchasing power. - Imagine today you have 1/100 of the total purchasing power, and then tomorrow the total money supply increases by 10 units. This means prices also go up 10% (over time) because there are the same amount of total real goods and services, but 10% more money chasing/pricing them. You now have 1/110 of the purchasing power. Just like that, instantly, the value of your money decreases in what it can buy. But this isn’t a purely economic issue; it means that you have fewer choices (expressions of preference) available to you, and will likely reduce your happiness if we carry through the idea from the first portion that the best thing we can do to “optimize for happiness” is maximize the ability for people to express their preferences through choice.

Inflation and the inability to save and plan for the future. - Inflation discourages saving because you know that your dollar today will buy you more goods and services than it will in the future. This causes a scenario in which people greatly discount the future because of their inflation expectation. This discourages investments that will bear fruit in the future, because potential future revenue is not worth the investment today. This inflation elevates preferences that provide short term benefits

The Cantillon effect. - This effect is much more impactful once Central Banking came into existence, but it is only impactful in a soft money world so I’ll include it here anyways. This effect speaks to the fact the new money isn’t immediately priced into goods and services. Let’s go back to the scenario where you have 1/100 of the total money supply, and therefore 1/100th of the purchasing power. Now let’s assume another person has 10 new units of money. Prices don’t adjust to this new money until the units are integrated into the economy; essentially, the 10% price inflation happens gradually as the new units embed themselves into the economy. This has 3 main implications in my view:

The person with these unintegrated units of money can purchase goods and services that are still priced as if there were only 100 units of money, a significant discount that compounds over time into a huge economic advantage. The person who spends these units first has the greatest discount, but because the price inflation is not instant, the path this new money takes into the economy leaves a trail of discounts to the spenders until it is completely priced in.

Your 1/100 slowly turns into 1/110, leading to the impacts discussed in the first two downsides: loss of purchasing power and short term thinking.

If a single person, or group of people consistently are the ones who first spend these new units of money, inequality will explode, as a small percentage of people can access goods, services and assets at a discount before the inevitable price & asset inflation sets in.

Before getting into today’s specific issues with inflation through the lens of central banking, I want to highlight the inherent volatile and irrepresentative circumstances centralized decision making leads to.

Centralized decision making creates volatile conditions

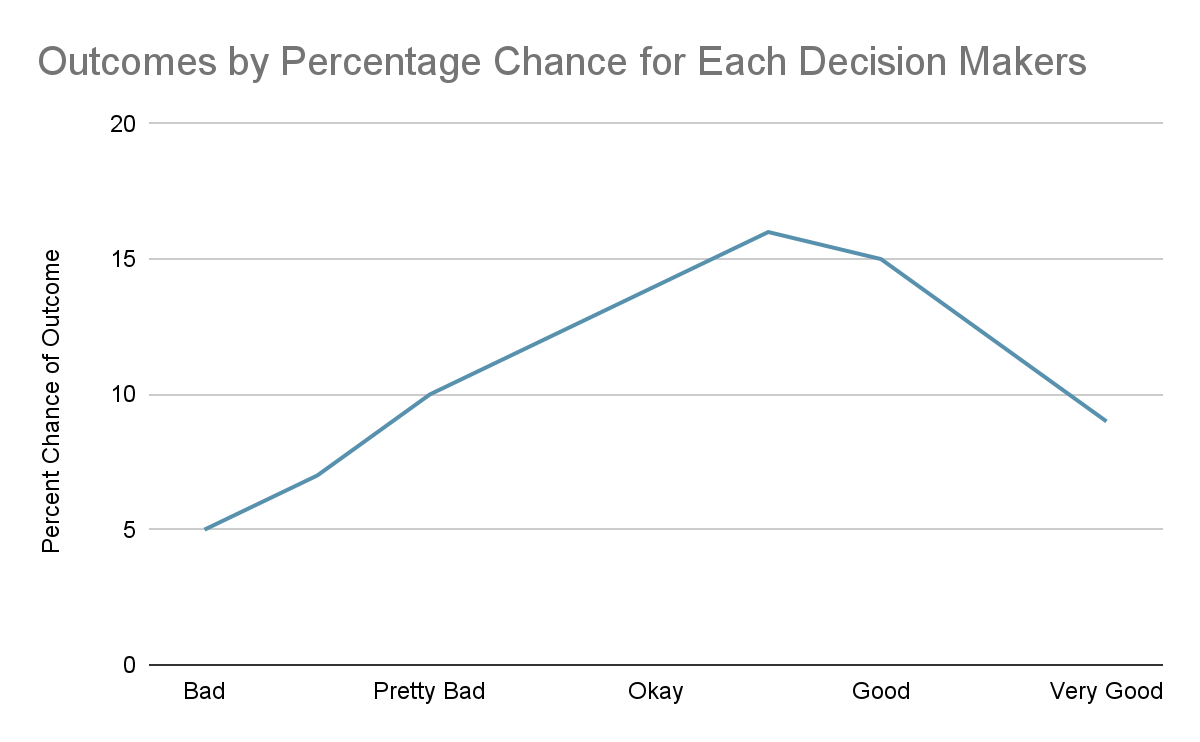

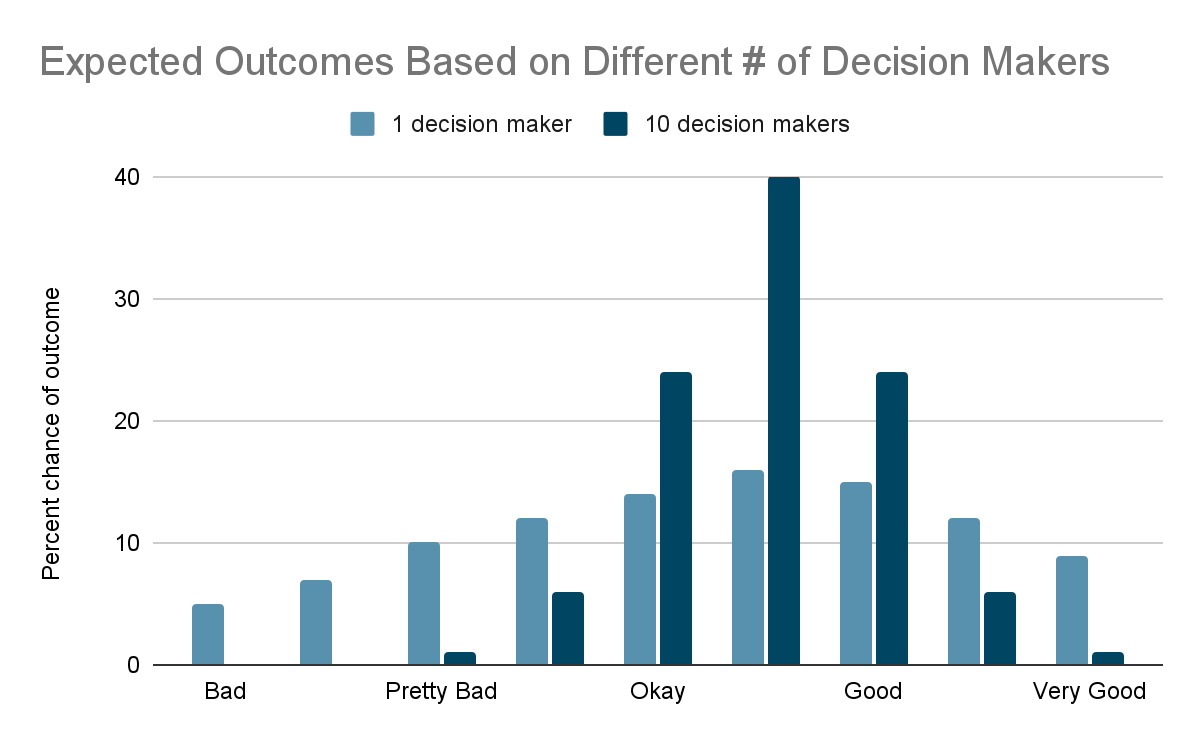

Statistically, the fewer events there are, the wider the average expected range of outcomes will be. Let’s take an overly simplified example of the economy. In this thought experiment, let’s assume the state of the economy is the result of the average quality of decisions made by 1 person, vs 10 people. Another way to say this is that in the first case, the state of the economy depends entirely on one person, while in the second each person has a 10% impact on the economy. Because the “strength” or “quality” of the economy is an immeasurable metric, let’s just assume we can differentiate good from bad on a relative scale. Let’s assume this curve represents the likelihood of each decision resulting in positive or negative scenarios.

Each decision maker has this distribution of potential impact on the economy as a result of their decisions (based on preferences). Now the two scenarios: if the economy is dependent on 1 decision maker, the likelihood of a “Bad” outcome is 5%, if the state of the economy is the result of 10 decision makers, the likelihood of a “Bad” outcome is effectively zero (0.05^10). This is the same for “Very Good”. This phenomenon is true for any system based on averages: the greater number of simulations run (in this case simulations can be equated to influential decision makers), the smaller the expected range of outcomes becomes. Note that the metric of the “state of the economy” here could effectively be anything. Price levels are likely a more realistic and applicable metric, and this explains why centralized price controls often lead to extreme shortages or surpluses. Nixon’s price controls in the 70’s are a clear example of this.

I haven’t completely run the numbers; but I think it’s safe to say the expected outcomes would look like something like this.

One could argue that a centralized decision maker gives the economy a greater chance of a very good outcome, but I think most people would agree that a stable, consistent, and reliable economy is preferable to a volatile one with a small chance for greater upside. Another reason stability is often preferable to volatility is because we as humans have more substantial negative emotional responses to bad news than positive emotional responses to comparable good news. (Kahnman and Taleb both explain this through studies). So far this is pretty abstract, but I think the easiest way to port this into reality is through interest rates.

It has become accepted that it is beneficial to economies to set their interest rate through their Central Bank. Based on the logic of the inherent volatility of centralized decision makers, I think this is wrong. The Fed sets the interest rate for interbank transfers that banks use to ensure they are meeting their daily mandated reserve requirement. This interest rate has knock-on impacts throughout the rest of the economy, as these banks then lend to people at rates that enable them to meet the interest payments on interbank transfer to remain solvent.

The interest rate can more simply be thought of as the price of money. If I want to take out a loan for $100 today, and the interest rate is zero, I can have $100 and have to pay back no additional cost beyond the principal $100 in the future. If the interest rate is 5%, then I get the $100 today and have to pay back the $100 plus $5 (plus compounding interest) in the future. (Side comment… but don’t 0% interest rates make no sense anyways? How would it make any sense that someone would want to give you $100 and then receive that same $100 back, but in the future. This makes even less sense in a world where we are literally targeting 2% inflation: the lender is by definition losing purchasing power on this trade. 0% interest rates are pretty clearly an unnatural phenomenon)

The two main points I’m trying to make are:

Prices are the result of markets expressing the preferences of all actors in the economy,

If economic metrics or targets (like prices or interest rates) are determined in a centralized way, the results will be volatile.

The price of money is just like any other price in the economy: it is most accurately reflected by the emergent price resulting from the preferences exuded by market participants, and when it is prescribed centrally, chaos ensues.

Changes in Central Banking in recent years

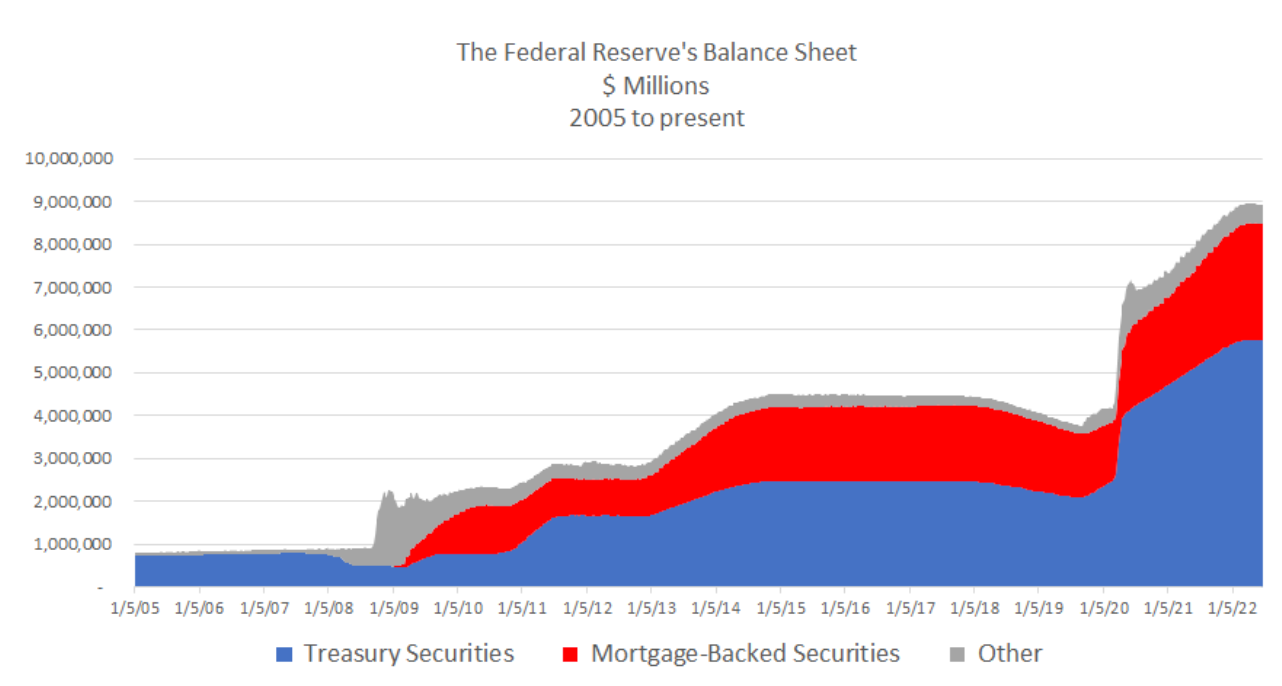

Historically the Federal Reserve’s mandate was to target 2% inflation and “full” employment by setting the interest rate through Open Market Operations. These OMOs initially consisted of the Fed buying or selling primarily US Treasuries on the open market. If the Fed is aiming to lower the interest rate, the Fed would buy Treasuries, therefore increasing the amount of money in the economy, making money less scarce. This lowers the cost of money by increasing the supply; and the cost of money is represented by the interest rate. The Fed would then reverse this transaction, or “decrease their balance sheet” by selling assets, to reduce the supply of money and increase the interest rate. This was the primary tool the Fed had for decades.

In response to the 2008 recession, the Fed used a new method aimed to stimulate the economy. This approach, called quantitative easing, is an approach that was developed to provide even more money and liquidity to the economy when the interest rates are already at 0%. In 2008 the Fed initiated their first ever round of quantitative easing. Quantitative easing (QE) is a similar mechanism to OMOs in that they both drive down interest rates through asset purchases, and therefore addition of dollars into the economy. The difference is the range of assets the Fed purchases through QE expands. The Fed began to purchase commercial assets like mortgage backed securities in addition to the traditional Treasuries. Just to be clear, these purchases are made with entirely new dollars! These dollars did not exist until they appeared on the financial statements of these commercial banks. This is how the majority of insolvent banks got bailed out in 2008. Final note on the assets the Fed buys during QE can be, and are in many cases, the same junk bonds and CLOs (Collateralized Loan Obligations) that caused the 2008 bubble and crash in the first place.

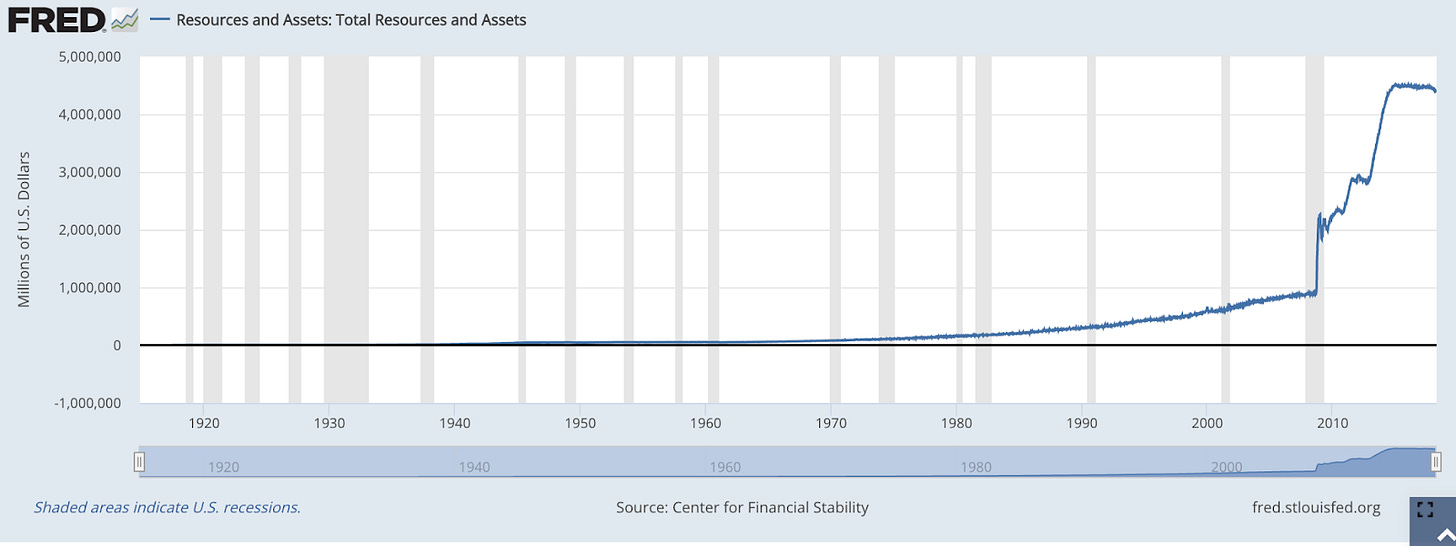

This chart visualizes the impact that this new “tool” of quantitative easing has had on the Fed’s balance sheet, which by nature also represents the number of dollars added into the economy. (How can we not expect inflation after looking at this chart?)

A more zoomed out view for perspective on the scale of this change in policy since 2008…

During the economic chaos as a result of Covid, the Fed again expanded their activities in an effort to directly fund small businesses. They launched a program called the Main Street Lending Program. This program was essentially a PR stunt by the Fed to show that they weren’t only bailing out Wall Street. I’m going to drop in a quote from “Lords of Easy Money” to describe this, because I don’t know much about it.

“(The MSLP) relied on local and regional banks to first make loans to small businesses, which the Fed would then buy. But the Fed also insisted that the local banks keep 5 percent of the loan value, meaning the banks had to absorb some risk. The banks were also deterred by the expense and work entailed with making loans to so many companies that might be in dire straits, with little chance of survival. The Main Street program had been built to purchase as much as $600 billion in loans. It had purchased a little more than $17 billion in loans by December, the month that it was shut down.”

While in the grand scheme of things the $17 billion is a drop in the bucket, I include this because it shows that the Fed is increasingly willing to expand the scope of their previously very narrowly defined activities, and to show that the bailouts only worked for the banks and large asset owners.

These practices of increasing the money supply through specific entities is a perfect example of why the Cantillon Effect is so impactful. The prices of asset, goods, and services don’t instantly increase with the Fed’s Treasury or QE purchases, so the first entities to spend these new dollars first benefit in a huge way. Those beneficiaries include Wall Street banks, Hedge Funds, and large asset owners. Those who are only slightly negatively impacted include the upper middle class who likely have a substantial portion of their net worth in investment/assets, that naturally inflate with supply of money. The people who get most economically damaged are the lower class; those with largely cash savings. Less purchasing power means fewer choices through which people can express their preferences, the foundational selling point of the free market in the first place.

Total M2 Money Supply since 2000. M2 is a measure of the money supply that includes cash, checking deposits, and easily-convertible near money. I won’t get into why CPI is a very manipulated and non-representative metric, but doesn’t total money supply increase seem like the most simple and accurate measure of inflation? This looks like more than the mandated 2% inflation target.

Unless we see a major change in Fed perspective or operations, we can expect the Fed to engage in a growing range of activities. The most scary potential development in my opinion is the development of a CBDC; a central bank digital currency. The Fed has been toying with this idea for a while, referring to the project as “Fedcoin”. This would complete the expansion of the Fed’s capabilities from simply targeting a prescribed interest rate through Treasury purchases, to each citizen having a digital account with the Fed. The implication of this would be massive. Imagine the $600 covid stimulus checks, but much more frequent, specifically targeted, programmable, and expirable.

I’ll stay away from many of the knock-on implication of this, and just point out the fact that if we think the Fed’s expansionary policy of the past 30 years has deprioritized the preferences of the vast majority of the population through inflation, a Fedcoin would all but eliminate the ability for citizens to have their preferences be seen through market prices.

____________________________________________________________________________

General Implications

What about political issues of today?

“If the Fed and government could facilitate the funding of, say, climate change mitigation technologies, wouldn’t that be a good thing?”

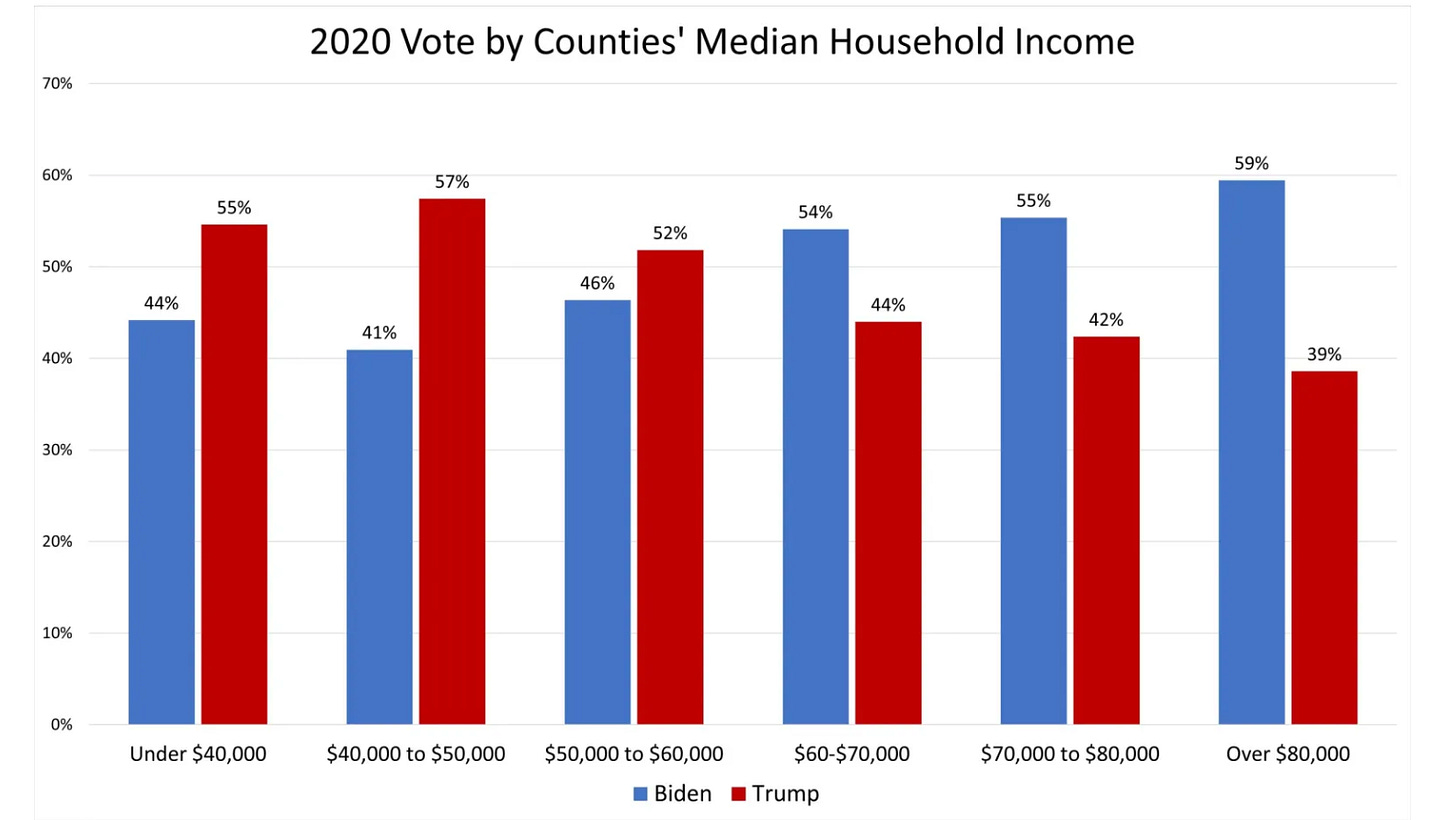

In a vacuum, the answer is yes, but in reality I think it’s much more complicated. I’m in full agreement with the liberal consensus that the economic inequality we see today is a danger to democracy. I just think the solutions proposed, that all involve massive spending, are far too divisive and top-down that they will fail to ever get large scale support until citizens themselves can afford to be concerned with the effects of climate change. For sake of simplicity, let’s assume that 50% of the population is living without enough savings to afford rent for the next 2 years. Is climate change top of these people's minds? No. Their time horizon is so short term oriented that there is no way they would prefer to pay higher taxes or endure purchasing power reduction through inflation (as result of Fed spending) in order to invest in a time further in the future they can afford to think about. I believe this is the core reason behind why we see the lowest income brackets dislike ideas like the Green New Deal. It’s not that they can’t see that climate change may be a severe issue in the future, but the problem is they can’t afford to think that far ahead; paying next month's rent is much higher on the list of priorities.. They prefer to focus on ensuring their rent is paid.

In the “utopia” that I see, we eliminate this wealth transfer via inflation that is the result of increased Fed spending. If we weren’t constantly devaluing the income of people through inflation, then they would be able to save. When one has savings, they can start thinking more about the future. Prioritizing the future becomes possible because people don’t need to worry about tomorrow. Their preference of how to spend their money changes from Walmart pizza to a new bike, a new degree, and maybe a new house. Once a substantially larger percentage of the population prefers to invest their resources in mitigating the effects of climate change, then it will naturally happen through our democratic process. It will be the preference of the people.

“But things would’ve crashed even worse if the Fed/government hadn’t intervened!”

This is true if we look at the direct aftermath of the ‘08 crash, and Covid too. The issue in my mind is that the reason that bubbles get so big is because of Fed policy and government bailouts. First, the recent Fed policy has been to hold interest rates at zero. This access to effectively free money encourages speculation. Banks and investors understand that if they get a free $100 (0% interest), and the true rate of inflation will be, say, 5%, they need to invest in high yielding businesses or assets to “beat” this 5% inflation. I think this is a big reason behind the wild tech stock fervor, the vast expansion of Venture Capital firms, Private Equity firms, and crypto scams. The second issue is ironic because this speculation is not an issue for big banks and companies. If their speculation fails, they are deemed “too big to fail”, and get bailed out. Occupy Wall Street was the first big movement that elevated this issue to the public. The less rosy reality of these speculative bubbles is that the individual, casual, and retail investors get hammered because they don’t get the bailout. The 2021 “meme stock” Robinhood fiasco is the best example of this.

I think it’s safe to say this is not a fair system. But what is the alternative? I don’t think the alternative is pretty in the near term, but the current system’s long term future is even uglier. We need a reality check. We cannot indefinitely bailout banks or businesses with uneconomic business models or investments. If we do, there will be no way to tell apart the businesses that are serving the preferences of the people, and those that are addicted speculators who get bailouts. The market naturally eliminates businesses that don’t serve the preferences of the people. It’s undeniable that if the government today made a public statement that they would no longer bailout anyone (banks, airlines, distributors, etc.) the economy would be a disaster, and real people would suffer no doubt. But businesses dependent on constant backstops and zero cost money will eventually be weeded out, and the scale of these speculative bubbles we’ve seen over the past 25 years would lessen substantially. There would be real risk for banks. One may call this a “consertavive” economic mindset, but I like to think of it as a simply realistic long term outlook. I’d love to hear a more compelling option for a prosperous future.

“Without interest rate setting wouldn’t it be the Wild West?”

I don’t think so. I think the biggest impact of eliminating the Fed’s target interest rate would be that growth (measured as GDP) would not be as high. But similar to my previous point on government intervention, this just means that growth was artificially high, and not representative of the real resources being produced and consumed in the economy.

Two additional notes on this topic.

Interest rates for loans for the average person and business are already dependent on the creditworthiness of the lendee. Therefore the biggest impact of eliminating the Fed’s interest rate manipulation would be on the banks conducting business with the minimum reserve requirements, a risky business in the first place.

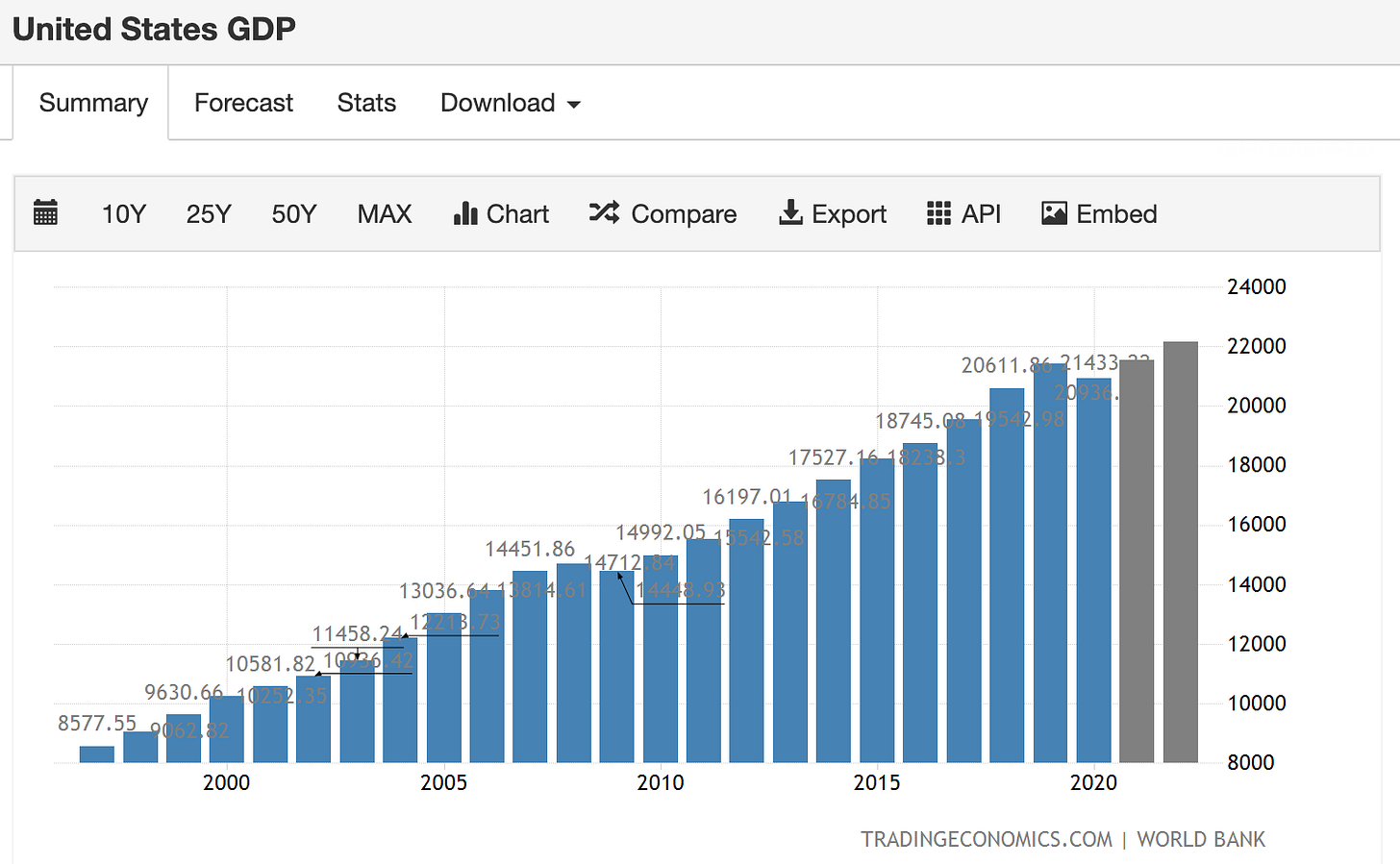

GDP is a blunt measurement that I think is so far removed from representing the wellbeing of individuals that it is all but meaningless. This is the recurring flaw in Keynesian thinking: macroeconomic measurements (GDP, CPI, PPI, Aggregate Demand/Supply) are so many steps removed from representing the happiness/preference of individuals that they, in my opinion, shouldn’t drive policymaking allegedly aimed at the wellbeing of citizens.

Were people twice as happy or well off in 2020 as they were in 2000?

What does this mean for our democratic system more generally?

Free market economy and democracy

Free market economics can reasonably be compared to democratic rulemaking. Each person makes their preferences known (through prices in the economy, and through voting in a democracy), and then people are incentivized to deliver on these preferences (businesses consisting of individuals in the case of the economy, and politicians in the case of the government). Those who deliver on these preferences most effectively are rewarded, financially for businesspeople and through re-election for politicians. Theoretically, in both systems the power lies in the hands of the people, as it should. I think it’s accurate to say that governments emerged in order to support, enable, and ensure faith in economic trade. Trade emerged before democratically elected governments, and from the start, a top priority of all democratic governments was to ensure strong property rights for their citizens. Democratic elections are the best way we currently have to make large scale, crowdsourced, “rulemaking” decisions that are designed by the people themselves. The idea that political “rules” are actually self-imposed feels very foreign in today's world. I’d like to see more “direct democracy” when possible, in contrast to “representative democracy”, but that’s a tangent. The key here is that governments need to stay in the “rulemaking” lane. Involvement in economics outside of tax collection/expenditure and bond issuance should be limited, as should money in politics. This is not a “tear it all down perspective”, I simply think that because Fed policy is not in any way a reflection of the preferences of US voters, they have no business having such a huge impact on our “rules”, let alone having an influence on our economy, the closest thing we have to a “database of preferences”.

Competition between democratic states is a feature

I think competition between states is good. All state and local governments must, by definition, have different policies than others. If they didn’t, then it would be very clear evidence that the “rules” are not being self imposed by the local constituents, but by the politicians onto the constituents. This is a critical difference, and leads me to believe that only essential and noncontroversial rules should be managed at the federal level. I haven’t thought through all the policies I think meet this noncontroversial level of consensus, but protection of property rights is a no-brainer. Strong property rights are essentially a prerequisite for society to evolve to the stage of having established states anyways. Any nonessential rules should be designed at the state and local jurisdiction level because the results of this smaller voting sample capture a much higher resolution understanding of constituent preferences than at the federal level. Statistically, the smaller the size of the voting constituency, the higher percentage of citizens will be living with “rules” they prefer. The same phenomenon of centralized price making doing a poor job of representing preferences applies to voting. If half of the nation's population supports a policy, and the other half doesn’t, a Federal policy will meet only half of these people’s preferences, while if each person were their own policymaker, everyone would be following rules designed to their preference. There is a happy medium between exclusively federal policymaking and anarchy that should be competitively reached by states implementing the rules that are voluntarily self imposed by their own constituents.

Political altruism cannot be depended on, especially without term limits

We cannot depend on altruism for those in power (elected or not) to make good decisions for society. Because both democracies and economies are expressions of their participants’ preferences, all asymmetric dependence on a single person’s preference should be avoided. This dependence should be avoided not only because we know that centralized decisions are inherently volatile, but also because this single preference is certainly not the most representative translation of the preferences of the population. In today’s America, there is an additional characteristic of our elected officials that exacerbates this problem: very lenient, or sometimes not-existent, term limits.

Think of it this way; while hypothetically, political actors are subject to the demands of their constituents, there is no way around the fact that policy makers always will be inclined to make decisions that are most beneficial to their own future prospects, as is the state of human preference. What is in the best interests of political actors changes drastically when we consider term limits and future career activities. If there are no term limits, a political actor’s preference will be to ensure a lucrative and dependable future for the country at large (which is good, all other things being equal), but in particular for political actors themselves. This is clearly not an accurate reflection of the preferences of the general population, of whom only a very small minority have political careers. Another result of long or non-existent term limits is that jobs on government or state sponsored payroll become increasingly attractive as it is in the interest of policy makers to prioritize the continuance and expansion of public offices if this is where they can spend their entire career. The result of this is a bloated, inefficient, administrative government and political system.

Let’s now imagine the incentives that are created by a political system with shorter term limits that guarantee policy makers will soon again be members of the non-politically employed populace. If a policy maker knows that in 6 months from now they will return to their previous job as a restaurateur, for example, it will be their preference to implement policy that prioritizes the wants and needs of non-political citizens rather than those of political actors. Another less direct and more qualitative benefit of this is that there will not be a substantial difference socially or economically between citizenry and political actors, as political actors are simply citizenry temporarily acting in this role.

This is not a new democratic idea: in Ancient Greek democracy, the Roman Republic, and the Republic of Florence, strict and non-negotiable term limits were the norm during their most prosperous periods. In Athens, a “boule” of 500 citizens was elected through popular vote to manage daily affairs of the city. These citizens were to serve for one year, and were limited to two terms. In the Roman Republic, a law was passed imposing a limit of a single term on the office of censor, a role with the responsibilities including the census and management of some government finances. Other political roles were elected for one year terms, including magistrates, the tribune of the plebs, the aedile, the quaestor, the praetor, and the consul, and were forbidden reelection until a number of years had passed. The most stringent term limits were placed on the “office of dictator”. While the dictator had a wide range of power, he was strictly limited to a single six month term. These strict term limits were eventually weakened, and ended with the end of the republic.

Stable long term expectations are paramount to long term prosperity

Stability is required for a society to have continued prosperity. This goes for economic stability and political stability (they are usually linked). I think that the slow erosion of our formerly sound money has ushered on the destabilization of our economy, society, and country.

Sound money is one foundational piece of the puzzle that starts to right the economic ship, and I think society follows. I don’t know how we eventually return to sound money, but I think it’s an inevitability; human preferences are too strong. The question is how do we return to an economy and world with stronger monies? Does the Fed change its tune and return to its initially prescribed limited role? Does a non-dollar currency slowly nudge the dollar away from its role as global reserve currency? Does an asset not issued by a sovereign country (eg. gold, bitcoin, other) become monetized as fiats continue to inflate without their dollar or gold peg? I’m not sure what will happen, but throughout history the most sound money always wins; we prefer it.