Deflation is Growth

As I’ve discussed before, I think our day to day discussions of the economic world are not very effective because they are built on a lot of assumptions that no longer reflect our economic reality. This divergence of economic theory and economic reality didn’t happen overnight, but slowly over the past 100 years or so.

The main concepts that sparked my interest in thinking through this essay are deflation and growth. My intuition is that growth and deflation go hand in hand: growth causes price deflation. This is the opposite of what is generally viewed as the relationship between growth and deflation. I started to think directly about this misalignment between my logic and the consensus view, but quickly realized the difference is likely the result of assumptions upstream of these concepts, rather than a fundamental disagreement or misunderstanding.

In this essay I’m going to identify base layer assumptions that are taken for granted in the current world of mainstream economic thinking. Then I will try to ignore these assumptions and start from the ground up to test their validity. This will help to flush out the initial question of deflation and growth.

To start, I want to share some statements that are uncontroversial in today’s mainstream economics world. In the category of “today's mainstream economics”, I include academia (Harvard, Stanford, pretty much all elite US universities), media (WSJ, NYT, Economist, Fox, etc.), and governmental and international organizations (Central Banks, The World Bank, IMF, WEF, etc.). The statements these organizations view as uncontroversial range from the topics of money, currency, economic management, desirable economic traits, and perspectives of economic phenomena.

I understand that there may be individuals at these institutions that don’t entirely agree with my generalized statement, but the point stands that the following views are generally not controversial.

Currency and money are, for all intents and purposes, synonymous.

Minimal price inflation (2%) is the ideal state of an economy over the long term.

CPI is useful in evaluating inflation.

Extreme price inflation is undesirable.

Any price deflation is undesirable.

Consumer spending and investment is a key and useful indicator of the health of an economy.

Price deflation is bad

I want to investigate each of these assumptions and try to determine how they emerged, whether they were and/or are still useful, and the implications of this assumption. First, let’s look at money and currency, because I think this is the most upstream assumption of the above list.

Currency and money are, for all intents and purposes, synonymous.

The public understanding of money and currency has converged almost entirely over the last century. Money can broadly be defined as any system of value that can be used as a medium of exchange and a store of value. Currency is a subset of money; currency is money that is officially accepted (and often issued or created) by a sovereign state or government. Currency can be used to pay taxes. Currency is to money as a square is to a rectangle; not all monies are currencies, but all currencies are money.

Successful and effective monies have always been physically challenging to inflate. I’ve written above this here so won’t rehash it fully, the point is that monies and currencies that have been easy to inflate, or “create” units of, have always rapidly depreciated in value, collapsed, and disappeared. Check out this list of old currencies and this list of current currencies.

Historically, successful issuers of a currency have ensured that trust remained strong in the value and scarcity of the currency by pegging the value of the currency to a hard asset. Gold was the main peg. This peg, in my view, was the key link that enabled currency to be a successful and reliable money. It was under this “pegged” view of currency that most assumptions underpinning current economic theory were developed. Keynesian economics, the foundation of “mainstream economics” as I alluded to above, was developed entirely during this period of currencies being “backed” by gold. This is key to keep in mind.

The implications of this are important. Keynes and Co structured theories of a demand-driven economy that could be stabilized with revenue-neutral government intervention. Keynes focused on policy to support short-term stability and crisis management through demand. Here’s a famous Keynes quote on the topic, and then another from Rand’s “looters” in Atlas Shrugged.

“The long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is past the ocean is flat again.” - Keynes

“‘It’s perfectly useless to theorize about the future’, snapped James Taggart, ‘when we have to take care of the emergency of the moment. In the long run –’... ‘In the long run we’ll all by dead’, said Meigs” - Rand as Washington insiders

I actually agree with Keynes’ prioritization of stability, but only given the assumption that countries’ currencies are pegged to a hard asset and cannot be arbitrarily inflated. When countries use revenue neutral fiscal policy to address short run issues that is one thing, but when countries can inflate their way out of “short run” turbulence, this negatively affects the long run. Keynes’ ocean won’t be flat again if we’re constantly increasing the amount of water.

When this background assumption goes out the window, it changes the logic entirely. These theories were developed before the US dollar (and all other currencies) formally de-pegged from gold. When a currency can be inflated without the consequence of defaulting on the peg to gold, one is dealing with a completely different asset. Using a theory that corresponds to a gold-backed currency is not transferable to one that is not backed by any scarce asset. One could compare this to using a 1950s small ball strategy in the MLB in the 2020s (outdated and suboptimal), but I think a more apt analogy is that this is like comparing 1950s 100 yard dash records to the 2020s, but we use a different stopwatch to time the runners in the 2020s - it is an entirely different sport we are playing.

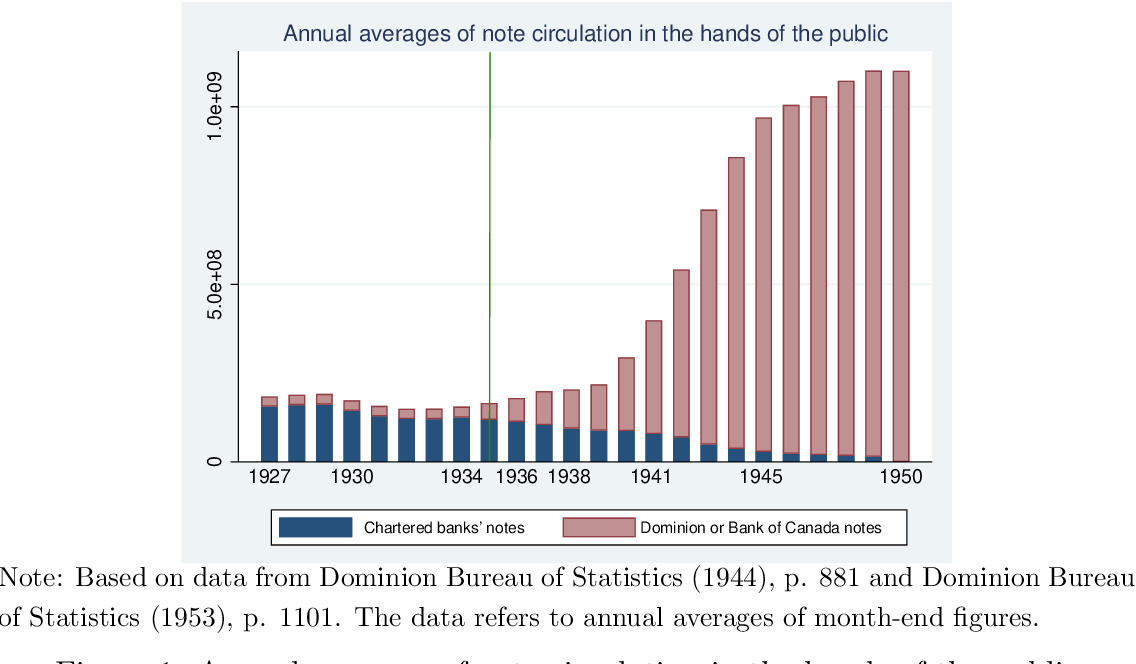

To make clear how drastic this shift in the meaning of “money” really is, let’s look at Canada. Before 1934, there was no Central Bank in Canada. Before 1934, there were what were called “Dominion” notes that were issued by the government and backed by gold, and there were private bank notes. We can see that private bank notes were used as the primary medium of exchange prior to 1934; this dynamic emerged naturally as citizens used the money they preferred. This turned out to be chartered bank notes, and then sometimes Dominion notes when government liabilities were owed.

This all changed in 1934 when Canada founded and enacted the Bank of Canada. This marks a clear and drastic shift in the composition of economic transactions in Canada. The Bank Act was passed in conjunction with The Bank of Canada, and restricted, and then formally disallowed the issuance of private bank notes. See the chart of this below.

This chart is from this paper: “Private Bank Money vs Central Bank Money: A Historical Lessons for CBDC Introduction”

This paper does a good job of describing the evolution from “private” to “public” money issuance in Canada over the revolutionary monetary period from 1920-1950. The author frames Central Banks as “competition” to private money issuance. While this is technically true, in my mind it is not fair to just describe it as fair competition because they do not compete with the same tools - one has the Treasury as a “phone a friend” and its creator can enact laws that ban its “competition”.

In my mind, it is not useful to use the same economic framework to analyze the pre-1934 Canadian economy and the post-1934 economy. One can just visually observe just by looking at that chart that something has changed in a big way. This same transition (from “liable private notes + backed public notes” to “no private notes + unbacked public notes”) happened across all major countries from 1913-1950. We can’t ignore this and pretend that “money” in 1910 is the same as “currency” today. This might be the most foundational error in mainstream economic thinking. The remaining assumptions I will look at are largely downstream of this.

2% inflation is the ideal state of an economy over the long term.

Before getting into this, let’s just observe the fact that in a world with a constant money supply, we would never view 2% inflation as ideal. 2% inflation in a hard money world means that demand growth is outpacing supply growth; this is obviously undesirable. Ok, onto today’s 2% inflation target.

“Low and stable” price inflation was the Fed’s mandated goal until 2012 when it formally identified 2% YoY price inflation as the target for the American economy. This is now generally accepted as an appropriate and rational goal that will help facilitate a strong economy.

First let’s define 2% price inflation, then determine what 2% price inflation means from first principles, and then look at 2% price inflation in the context of how it impacts us today.

First, what is 2% price inflation? This means that on average, the cost of goods and services increases at 2% nominally every year. By definition, this means we would expect a unit of currency to buy half as much 35 years from now compared to today.

Note that price inflation is different from monetary inflation. Generally, we can think of two different price inflation equations that intertwine to show the complexity involved in price inflation. See simplified formulas below.

Price Inflation = Demand Growth / Supply Growth (assuming the monetary base and production efficiency remains constant)

Price Inflation = Monetary Base Inflation / Production Efficiency Gains (assuming demand growth and supply growth remain constant)

While both of these equations make sense in their respective vacuums and holding everything else equal, things get very complicated when all four variables change. Unsurprisingly, reality is complicated, so that is what happens.

One could combine these and think of Price Inflation as the following:

(Demand Growth & Monetary Base Inflation) / (Supply Growth & Production Efficiency Gains).

Note that all of these metrics except for Monetary Base Inflation will vary by product or service in the economy. For example, demand could grow for cars while falling for houses. This phenomenon is true for changes in “supply” and “production efficiency” also. Changes in the monetary base (the total number of units of money) is the only measure that affects the entire economy because all goods and services use this metric as a measuring stick for prices.

This is important, because it shows that to successfully “target” a specific price inflation metric there are four variables that need to be managed concurrently to result in a stable price inflation year over year. I’ll come back to the question of how one can even think about trying to target a specific rate of price inflation given these four variables, none of which can be completely controlled… But first, let’s think about what the true impacts of inflation and deflation are.

To think about these impacts clearly, I want to separate the thought experiment into inflation caused by all different causes: demand growth, supply reductions, monetary base growth, and efficiency losses.

For the purposes of these examples, we need to assume that the other three measures other than the one of interest are held relatively constant. Also, I’ll note that each of these changes had a prior cause, so the first few bullets I’ll describe what can cause each type of inflation prior to digging into the impacts of the inflation itself. So with those assumptions in mind, what are the impacts of price inflation caused by…

…Demand growth?

This kind of demand growth is caused by shifts in customer preferences. Think of the demand for seasonal goods (pumpkins, jackets, sunscreen, etc.)

An increase in the market price for specific goods & services due to demand growth will encourage production of these goods and services because they will have become more profitable business ventures as the sale price increases while cost of production remains the same.

This production increase will help “balance” the demand / supply ratio, and assuming demand growth doesn’t continuously outpace supply growth over time, prices will eventually fall again.

This is a balancing mechanism, and is the core of how a market functions.

Price inflation due to demand growth has never been a long term phenomenon, because we have always been able to increase supply or production of goods and services at, or above, the pace of demand growth in the medium to long run.

Overall, inflation due to demand growth is natural, and should not be viewed as a bad thing.

…Supply reduction?

Similar to demand increases, supply reductions occur on a good by good basis. Supply of some goods can fall at the same time as supply of others increases; we need to frame these impacts through the lens of a single good or service.

This generally would happen due to a breakdown of the production or delivery capacity of a good or service. Think the energy (natural gas) shortage in Europe last year causing electricity price spikes (1), or the avian flu in the US this past year causing the price for eggs to increase substantially (2).

When prices rise as a result of supply reductions, the same incentive emerges for producers/providers of the good or service of interest as when demand increases. An increase in the market price for specific goods & services due to supply reduction will encourage production of these goods and services because they will have become more profitable business ventures as the sale price increases while cost of production remains the same in short to medium term.

Also similar to demand growth, price inflation due to supply reduction is a natural occurrence, is not a long term phenomena, and reveals incentives that will help to “rebalance” prices.

…Efficiency losses?

Inflation due to production efficiency losses are generally rare. Most of the time, efficiency gains actually cause deflationary pressures because we almost always get better at doing things over time.

But for the thought experiment, there are times when efficiency losses emerge naturally, or through geopolitical actions.

A company could implement a new operational strategy with aims to create cost efficiencies and the opposite could happen… I feel as if I’ve experienced this in some of my jobs, and have heard of others experiencing the same phenomenon (cough.. An oil major?)

Efficiency losses due to geopolitical tariffs and policy (both domestic and international) can negatively impact the efficiency with which some industries can operate. All government incentives cause efficiency losses in the short term (one could debate the long term impacts…). Some clear examples that come to mind include the tariffs on Southeast Asian solar panels, and the hilariously named Inflation Reduction Act that passed last August that provides massive Tax Credits to technologies deemed worthy by the government. This causes efficiency losses because it shifts mental and physical energy and resources from the true economically efficient solution to others that now appear economically competitive due to the incentives. I could go on and on here… but will cut the rant short.

Regardless of how efficiency losses emerge, the impact is a higher cost of production per unit of output, and this forces businesses to increase their prices to maintain profitability.

The impact of this is that demand for these services will fall, and the market will be incentivized to regain the efficiency that was lost through other means.

Regardless of the cause of efficiency losses, the resulting incentive to regain efficiency of production of the good/service of interest, while demand falls off some, will help “rebalance” prices. I imagine you are noticing a trend here…

…Monetary base growth?

Monetary base growth happens when the total numbers of units of money or currency increases. Prior to fiat currencies, monetary base growth happened when more gold or silver (or any other monetary medium) was discovered, “mined”, and incorporated into the economy.

Now, with fiat currencies, the number of units of currency can be increased through the treasury and central banks. For reference, in 1959 there were $287B in circulation, now there are $20,900B. This data shows monetary base growth in action.

The major difference between monetary base growth and all other causes of price inflation is that monetary base growth affects all goods and services. While demand increases, supply shortfalls, and efficiency losses (and the resulting inflation) necessarily occur on a good/service basis, an increase in the monetary base affects the prices of all goods/services equally, not on a good by good basis. This results in macroeconomic incentive changes that affect consumer and producer decision making across the entire economy rather than on specific goods/services.

Inflation caused by monetary base growth encourages spending in the near term, and raises the time preference (value of today / value of future) of individuals because a single unit of currency will be able to purchase fewer goods and services in the future.

There are two main points of this section I want to highlight.

2% price inflation is an incredibly complex metric that tries to summarize the independent price action of countless goods and services into a single number, and doesn’t have a good reason for “why 2%?” behind it.

Because demand growth, supply reduction, and efficiency losses are all good/service specific and emergent phenomena, the only real tool governments and central banks have to target 2% inflation is monetary base growth.

Consumer spending and investment is a key and useful indicator of the health of an economy.

GDP is generally considered to be a reasonably useful approximation for the wellbeing of a country’s economy. GPD, as measured by “the expenditure approach”, adds up the value of purchases made by final users—for example, the consumption of food, televisions, and medical services by households; the investments in machinery by companies; and the purchases of goods and services by the government and foreigners.

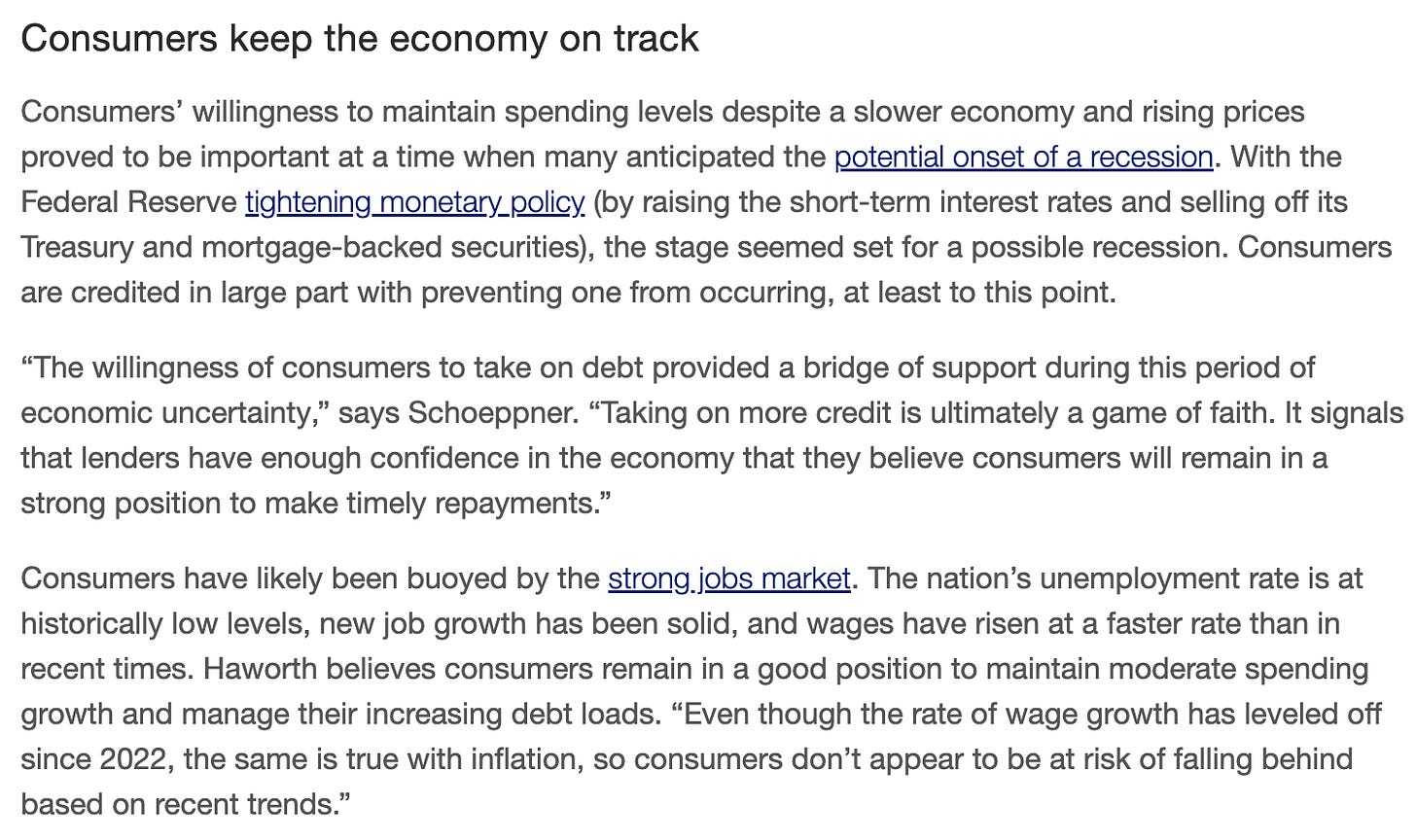

Below is an excerpt from a US Bank article on the state of the US economy in Sept 2023. This article is pretty annoying to me; just because consumers seem like they may be able to pay off their debts doesn’t mean their spending is good, let alone optimal!

I’ve discussed before why GDP is not a good representation of a population's wellbeing (here). Now, I want to expand on this idea to make the point that there are times when lower consumer spending and investment should be more preferred than higher spending and investment. Said another way, sometimes a low GDP is better than a high GDP.

The main reason for this is malinvestment is worse than no investment.

This statement, I hope, doesn’t seem too controversial, but I think it is unfortunately quite relevant to the US economy over the past 20-30 years.

To break down this claim, we need to think about how we evaluate the quality of spending or investing. In my view, a good investment is anything that produces a positive real rate of return. This means that over time, the real value provided to others is greater than the resources invested into the good or service. While this sounds simple, in an economy with arbitrary money supply increases and politically determined interest rates, incentives and price signals become incredibly convoluted, and understanding the quality of an investment becomes nearly impossible.

It is hard to see “malinvestments” when they are made, but it becomes quite clear when they are exposed, as all eventually are. These malivestments can come in many forms, but the two clear examples of how they reveal themselves include speculative investment bubbles, and stock market crashes. Think of the irrational Gamestop and AMC stock chaos of 2021, and the seemingly regular market crashes we’ve seen consistently since the 1980s.

In reality, what is a stock market crash? It is the realization of a colossal amount of malinvestment that has been built up for years. Eventually someone is always left holding the bag of a bad investment, it can’t be escaped: reality wins.

Chronic widespread malinvestment is the result of inorganic and clouded economic conditions. While these conditions are the results of many things, in my mind there are two causes of high malinvestment and irresponsible spending metrics over the past 20 years.

Zero percent interest rate (ZIRP) policies.

Monetary base inflation has increased our collective time preference.

Because I think these two phenomena impact our spending and investing slightly differently, I’ll address them separately.

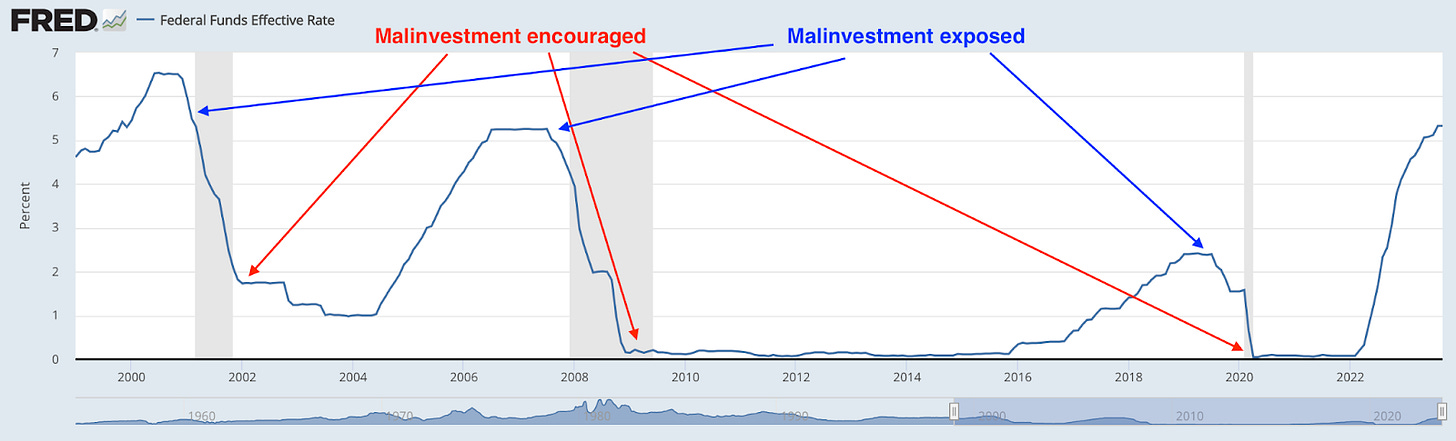

The Fed first introduced a ZIRP policy in 2009 after the ‘08 crash. ZIRP policy by the Fed artificially lowers the cost of borrowing money. In a world with an inflating monetary base like the US, the real cost of borrowing is never zero. (why would anyone lend $100 at an interest rate less than the rate of monetary base inflation?) But, businesses make decisions in the economy they are operating within. If a business model pencils with the interest rate available to them, the business is going to invest because it is better than doing nothing with your dollars. That being said, just because an investment has a >0% nominal rate of return, this does not make it a good investment.

In fact, I think most malivestments that have been exposed over the past 20 years are the result of investments made with artificially low interest rates that make positive nominal returns, but negative real returns. These ventures with negative real returns are exposed when the inflation required to keep up the ZIRP policy inevitably starts to creep into the economy. Then, to make matters worse, the Fed is forced to raise rates to curb inflation, making “saving” these failing businesses even more expensive because the cost of borrowing has gone up. In my view, this is a pretty clear cycle that we’ve fallen victim to consistently since the ‘80s.

Check out this chart below with my markups to show when I think ZIRP policy encouraged malinvestment, then when it blew up in everyone’s face.

This chart is pretty concerning if you look at the stability of businesses that were either supported through the Covid crash with government funds, or businesses that were established in 2020-2021. They invested into a business when the cost of borrowing was low, and now it is 5%. The question is how long can today’s businesses that are teetering continue to operate without extreme economic fallout?

I’m going to go on a little tangent here to frame the idea of “ malinvestment is better than no investment” in Pirsig’s MOQ framing. I think the mainstream economic perspective that “investment = good” can be ported into MOQ by saying “investment = dynamic social patterns of value”. For the mainstream economists’ perspective to be accurate, all dynamic social patterns of value must be desired and beneficial. While this may be true in the near term, and MOQer would realize that dynamic social patterns don’t always expand upon or improve the social pattern of values, but can in fact disrupt and devolve these static patterns. I think that is what is happening at a huge scale today.

In my view, malinvestment is a dynamic social pattern of value that undermines the static social patterns of values, while a good investment is a dynamic social pattern of values that strengthens and expands upon the static layer it is built upon. With this framing in mind, you can see why I could imagine how a lower GDP could be more optimal than higher GDP: if the GDP consists of malinvestment.

One of the most eye-opening examples of malinvestment that has been on display is the Chinese real estate market. Read the full summary here, and WaPo’s take here. Long story short, Chinese policy was encouraging domestic growth through real estate development by giving developers loans at wildly low rates. This clouded the real cost of development and the real demand of real estate. Eventually, it became clear that developers drastically overbuilt and were left with no revenue to repay the massive loans that they took out.

One last excerpt on this topic from Atlas Shrugged that I can’t help but include, especially with the Chinese real estate debacle in mind.

“There is no conflict, and no call for sacrifice, and no man is a threat to the aims of another - if men understand that reality is an absolute not to be faked, that lies do not work, that the unearned cannot be had, that the undeserved cannot be given, that the destruction of value which is, will not bring value to which isn’t.” - Rand as Galt

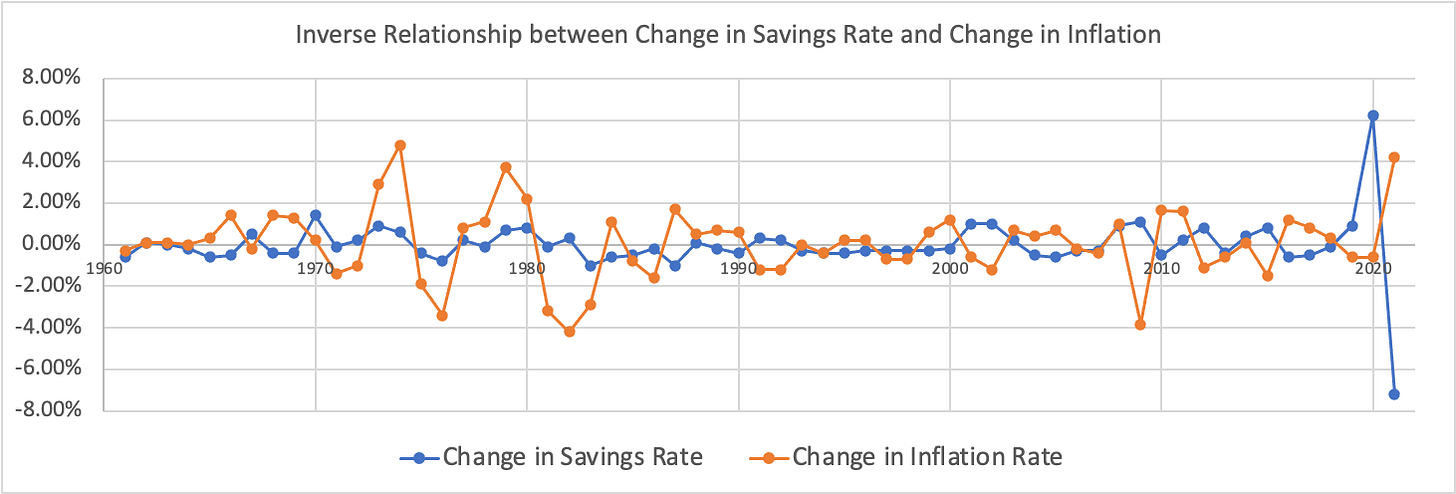

Okay, onto the second cause of malinvestment, monetary base inflation. I think while ZIRP policy affects businesses more directly than individuals, monetary base inflation affects the spending choices of all of us. Monetary base inflation increases our time preference, and reduces the incentive to save money. This means monetary base inflation makes us focused on the short term, and encourages us to spend money sooner rather than later. Let’s look at some interesting charts.

This chart shows an admittedly tenuous, but I think still useful, relationship between the change in the inflation rate, and the change in the household savings rate in the US. The relationship observed is as inflation increases, the household savings rate decreases. This can be seen as a quite consistent trend since 1990. This also makes logical sense: when inflation increases, your currency will buy less in the future, so you rationally would save less and spend more today.

Let’s look at a real example that I imagine we can all relate to in some way. Furniture. Old furniture was built to last. Today’s furniture is cheap and doesn’t last long; it is almost disposable by design. What’s up with that? What caused this change?

While I agree with the frustrated sentiment that this recent WaPo article expresses in a recent article on this topic, I don’t think corporate profit motive is the sole guilty force as they report. After all, businesses are just responding to incentives and the market they are operating in. I think a more accurate storyline is this: customers started demanding more low cost furniture, so businesses started manufacturing low cost furniture. This reveals the obvious question; why did people start demanding more low cost/quality furniture? Monetary inflation is a good answer to this question.

The higher monetary inflation is, the lower the incentive to save is. Said differently, the higher monetary inflation is, the greater the incentive to spend now. When we are not incentivized to save, society tends to not purchase cheap goods in the near term rather than save up and buy a quality good in the future.

I think this is a sound explanation for why the quality of precious durable and long lasting goods have become cheaper and lower quality. This trend of quality deterioration can be seen across many industries. Saifadean Ammous wrote an entire book on this concept called “The Fiat Standard”. While one could make fair criticisms that he makes some claims that aren't entirely provable, there is no doubt that his underlying thesis that inflation of fiat currencies increases people's time preference is valid.

This article by Vox has another explanation that is comparable to the WaPo explanation. While I think it is a more widely accepted answer to the same question of “why did people start demanding more low cost/quality (insert any good)”, I unsurprisingly disagree with their answer. Their answer boils down to this quote, “At the same time, the blame (for lower quality goods) does not lie on consumers’ shoulders; corporations are responsible for creating and stoking the “new and more is better” culture we have today.”

As I described before, I think this is a cop out. At the end of the day, consumer preferences always drive the incentives for what corporations’ produce. While it’s true that more targeted and advanced advertising and cultural changes sway some decision making, more fundamental underlying macroeconomic incentives are driving this widespread change in consumer preference.

It’s not the corporations' fault; they are just responding to consumer preferences. It’s not the consumers’ fault; they are just responding to macro economic incentives. What macroeconomic metrics change consumer preferences for all goods and services at the same time? Monetary inflation. Think back to the causes of inflation. Monetary inflation is the only single metric that affects the entire economy at once.

Ok, so I clearly think monetary inflation is undesirable. Are there any challenges with deflation? After all, most mainstream economists today are very scared of deflation.

Price deflation is bad?

There are many commonly raised concerns about dangers that economies experiencing deflation will face, but in my opinion most arguments that underpin reasons to fear deflation are downstream of the following two ideas.

Persistent deflation will eventually require wage decreases

Deflation is bad for debtors and will decrease investment and spending

I do not disagree with the validity of these two statements themselves, I dispute the underlying assumption that they are bad.

While it’s true that as we get more efficient at producing goods and services in a 0% monetary inflation world wages will have to fall, this doesn’t mean employees are getting poorer. As long as price deflation exceeds wage decreases everyone is better off. We just are not used to this dynamic.

We are much more used to wage growth not keeping up (or barely keeping up) with monetary inflation, which is optically palatable (“I got a raise!”), but in reality detrimental for one’s purchasing power. While the first bullet above may seem scary, it is much more of a social and cultural norm disruptor than an economic danger. Purchasing power is what matters, not nominal wages.

To the second point on deflation being bad for debtors. Let’s break this into two pieces 1. Spending and investment will decrease, and 2. Deflation is back for debtors.

The first statement is true, but I don’t think this is inherently a bad thing. Not all spending and investment should be viewed as good. I think a deflationary economy helps to parse out and disincentivize two types of spending/investment that we shouldn’t want. First, price deflation discourages the cheap furniture scenario I described above. Rather than encourage the purchase of cheap non-durable goods, deflation encourages saving and then purchasing only long lasting, quality goods.

The second type of investment price deflation discourages is malivestment. In a deflationary world, there would be no investments that make positive nominal returns but negative real returns. This “good investment” illusion that has been prevalent and arguably the cause of each of the market booms and crashes since the ‘80s would not be possible in a deflationary world.

The second statement regarding deflation’s impact on debtors is true, particularly for long duration debtors who borrowed money with the implicit assumption that inflation will continue in the future. While it’s true this includes the vast majority of debtors in the world today, we need a reality check, as I’ve described here. The challenge with this is that the entities that stand to lose the most from this reality check are governments. Here is a good chart to visualize the sovereign debt that is owned by governments around the world.

The implications of this observation are pretty severe in my opinion. Thinking through the logic behind these fears of deflation makes one observe that the interests of governments’ financial solvency are directly opposed to the economic interests of the people. Governments require monetary base inflation in order to not explicitly default (they are already defaulting in real terms) on their debts, while monetary inflation is continuously chipping away at the purchasing power of these countries’ citizens.

I gamed out the sovereign debt scenarios previously, and “inflate the debt away” emerged as the most palatable option from the governments’ perspective; is in large part why deflation is so demonized.

Takeaways

Money and currency are not synonymous, and have diverged in meaning since the early 1930s (think the Canada example)

Price deflation is natural, and would occur in a hard money world

Monetary inflation is the only cause of inflation that affects the market for all goods and services simultaneously

Malinvestment is worse than no investment

Inflation encourages near term spending, deflation encourages near term savings

Inflation encourages speculative investment, deflation encourages careful investment